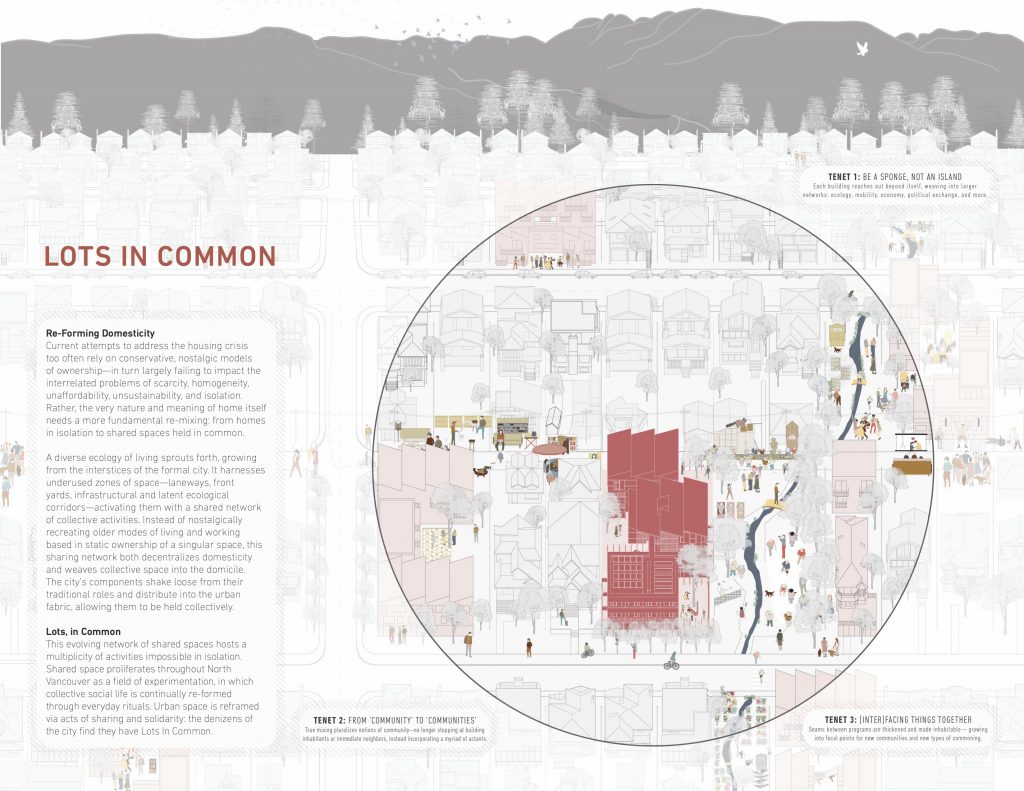

Lots in Common

First Prize, Mixing Middle Competition | Urbanarium, Vancouver | 2022

Collaborators: Roy Cloutier, Nicole Sylvia, Lőrinc Vass

Re-Forming Domesticity

Current attempts to address the housing crisis too often rely on conservative, nostalgic models of ownership—in turn largely failing to impact the interrelated problems of scarcity, homogeneity, unaffordability, unsustainability, and isolation. Rather, the very nature and meaning of home itself needs a more fundamental re-mixing: from homes in isolation to shared spaces held in common.

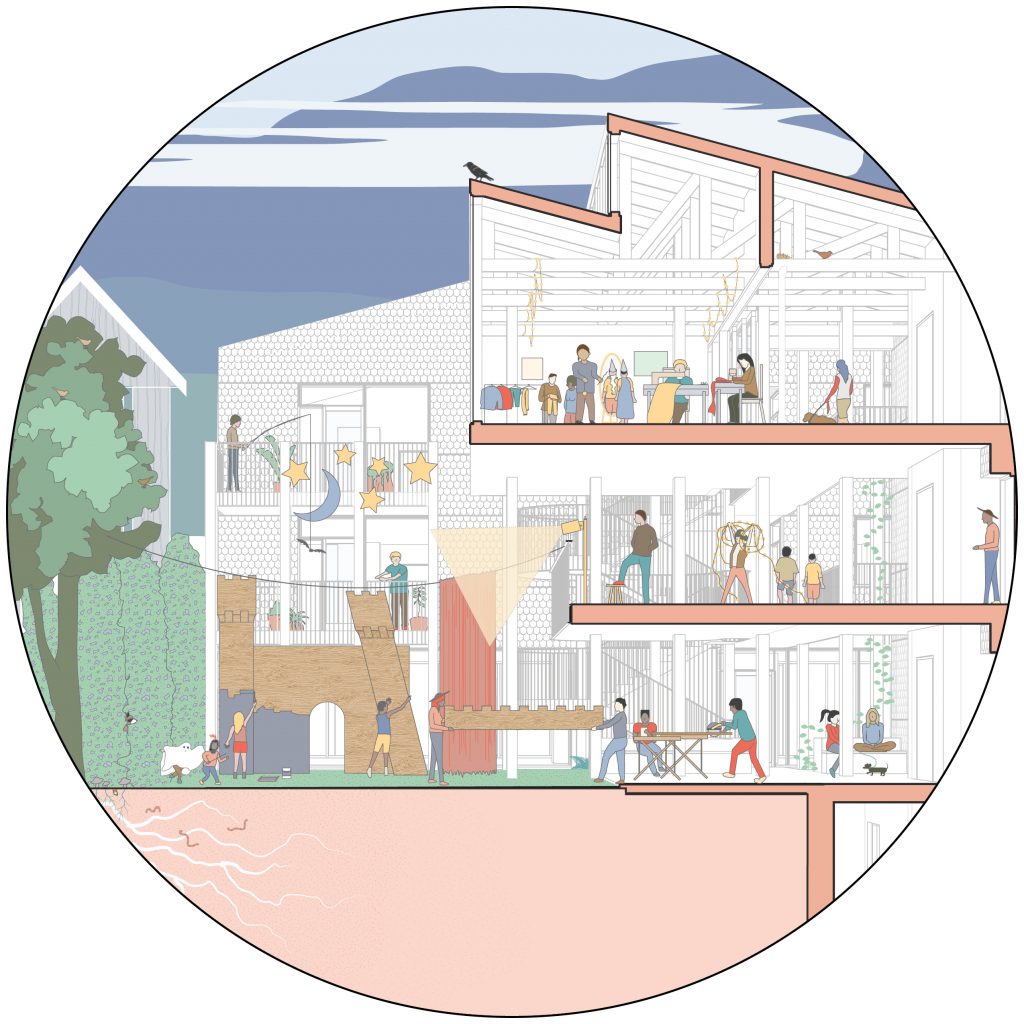

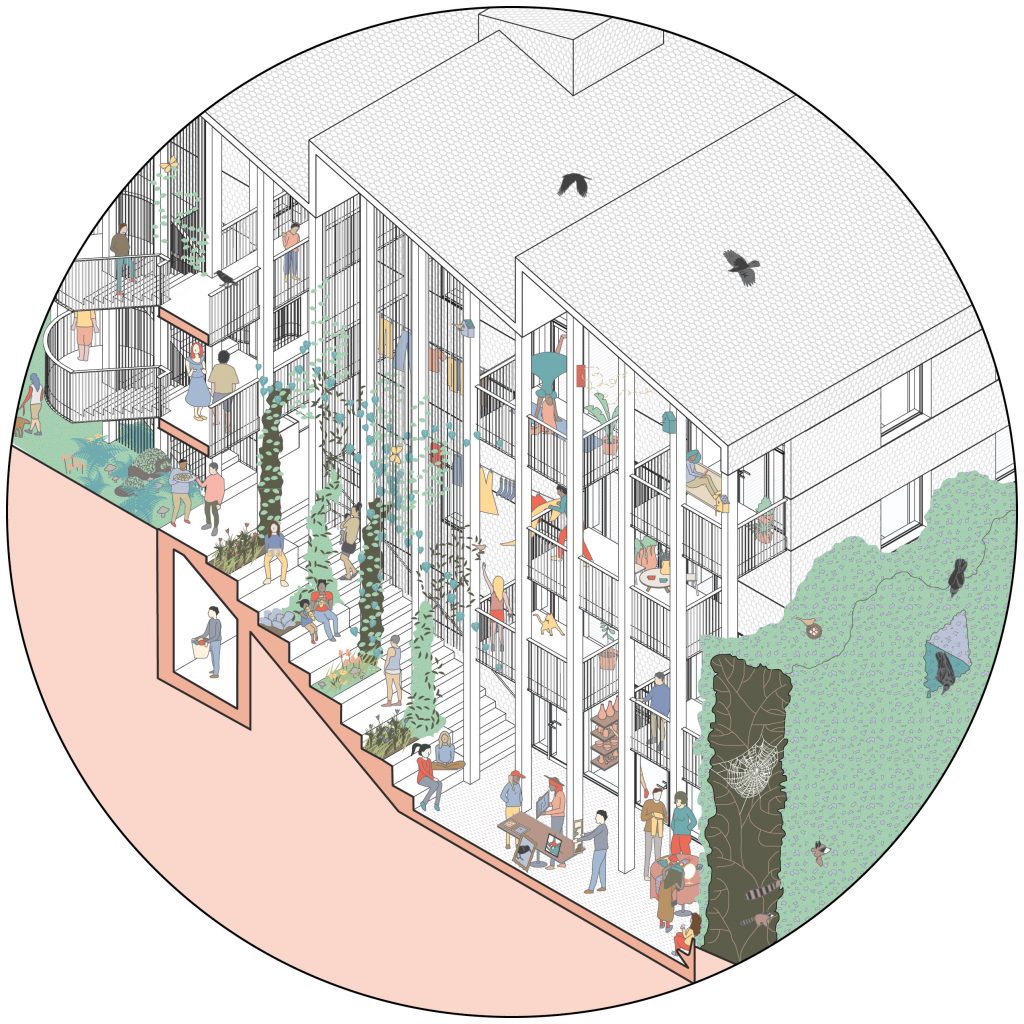

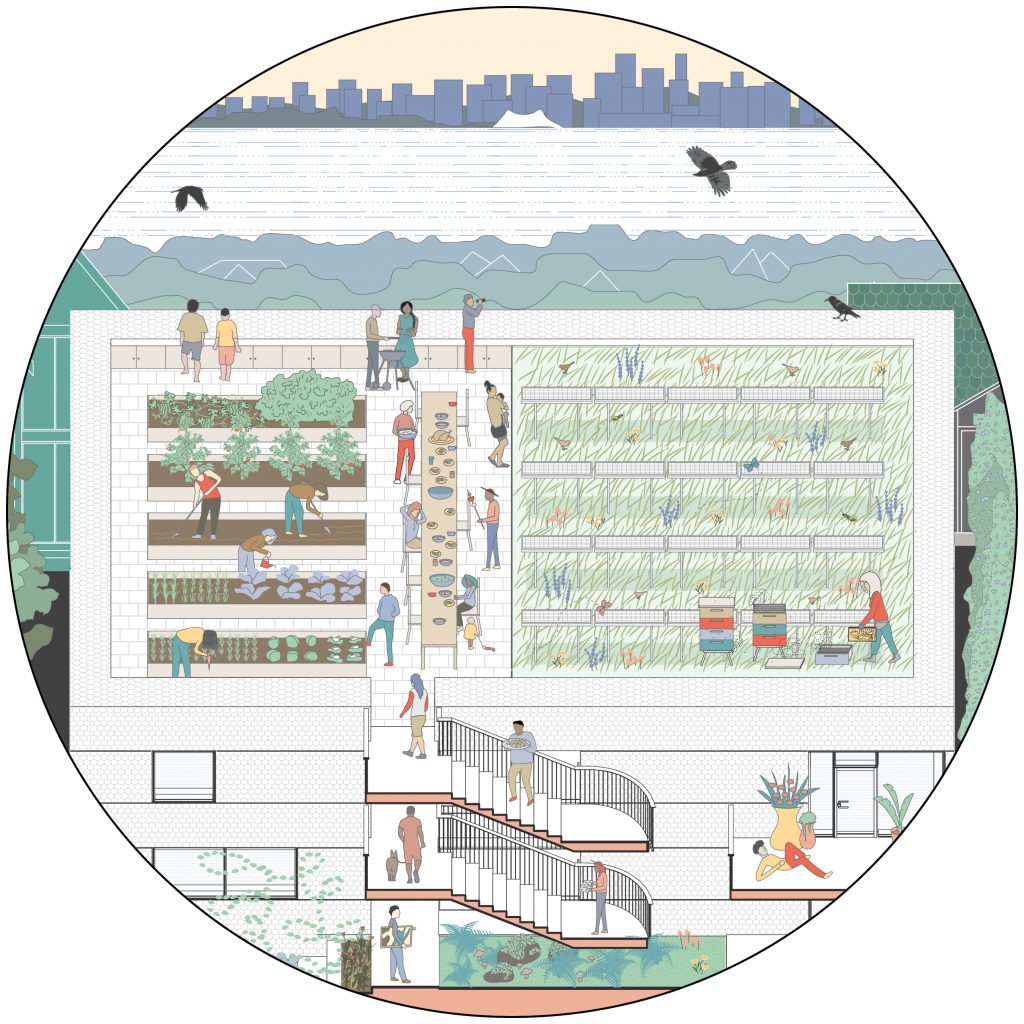

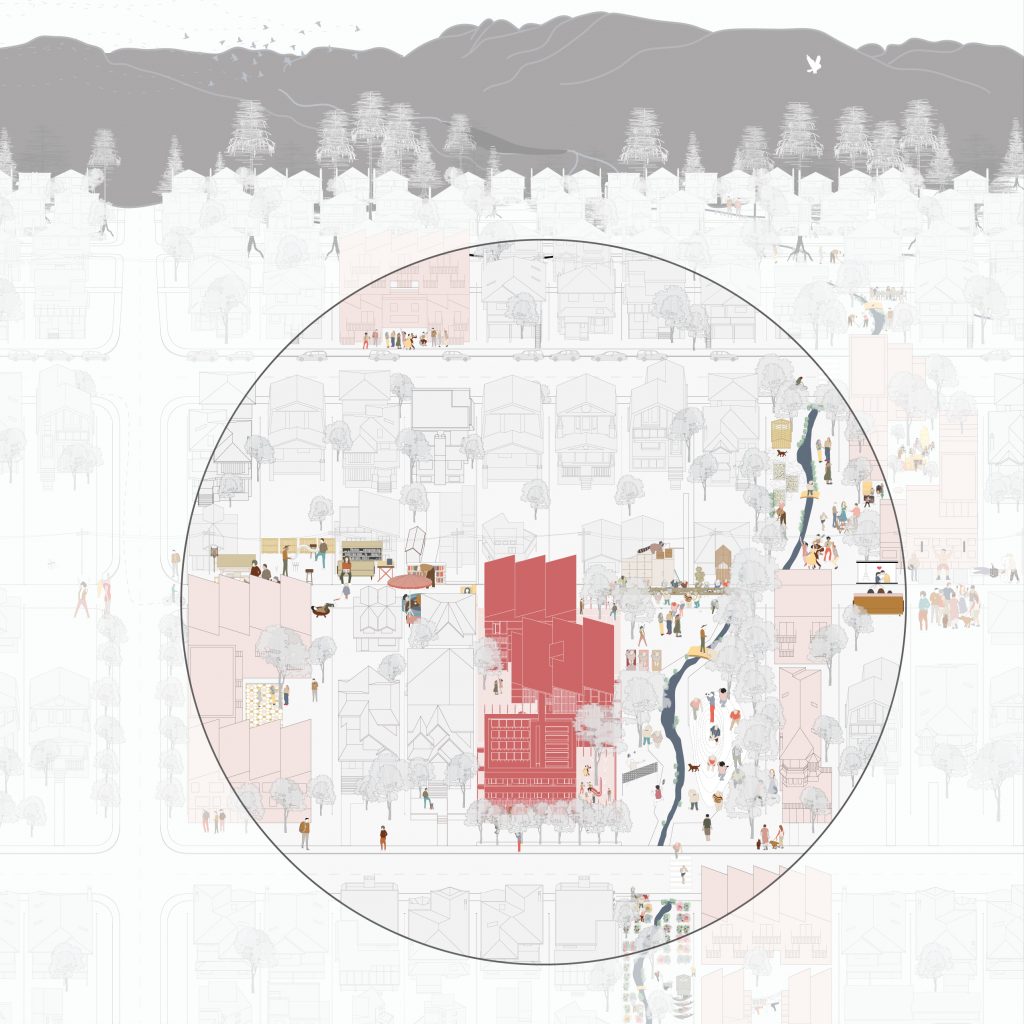

A diverse ecology of living sprouts forth, growing from the interstices of the formal city. It harnesses underused zones of space—laneways, front yards, infrastructural and latent ecological corridors—activating them with a shared network of collective activities. Instead of nostalgically recreating older modes of living and working based in static ownership of a singular space, this sharing network both decentralizes domesticity and weaves collective space into the domicile. The city’s components shake loose from their traditional roles and distribute into the urban fabric, allowing them to be held collectively.

Lots, in Common

This evolving network of shared spaces hosts a multiplicity of activities impossible in isolation. Shared space proliferates throughout North Vancouver as a field of experimentation, in which collective social life is continually re-formed through everyday rituals. Urban space is reframed via acts of sharing and solidarity: the denizens of the city find they have Lots In Common.

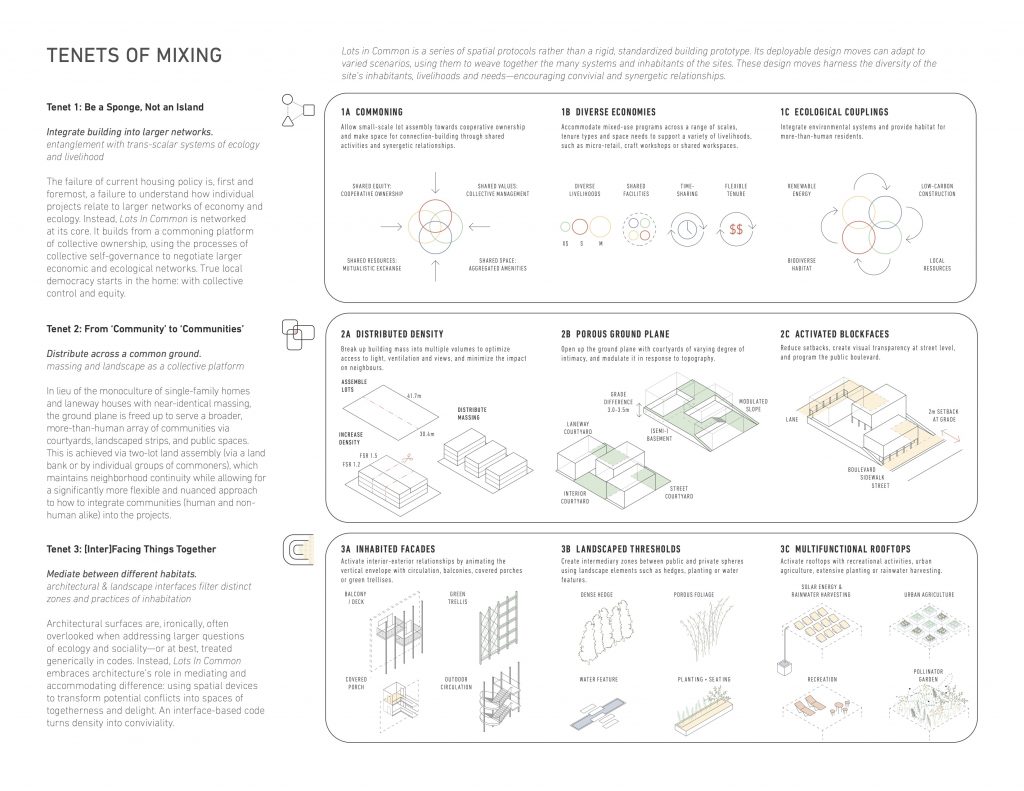

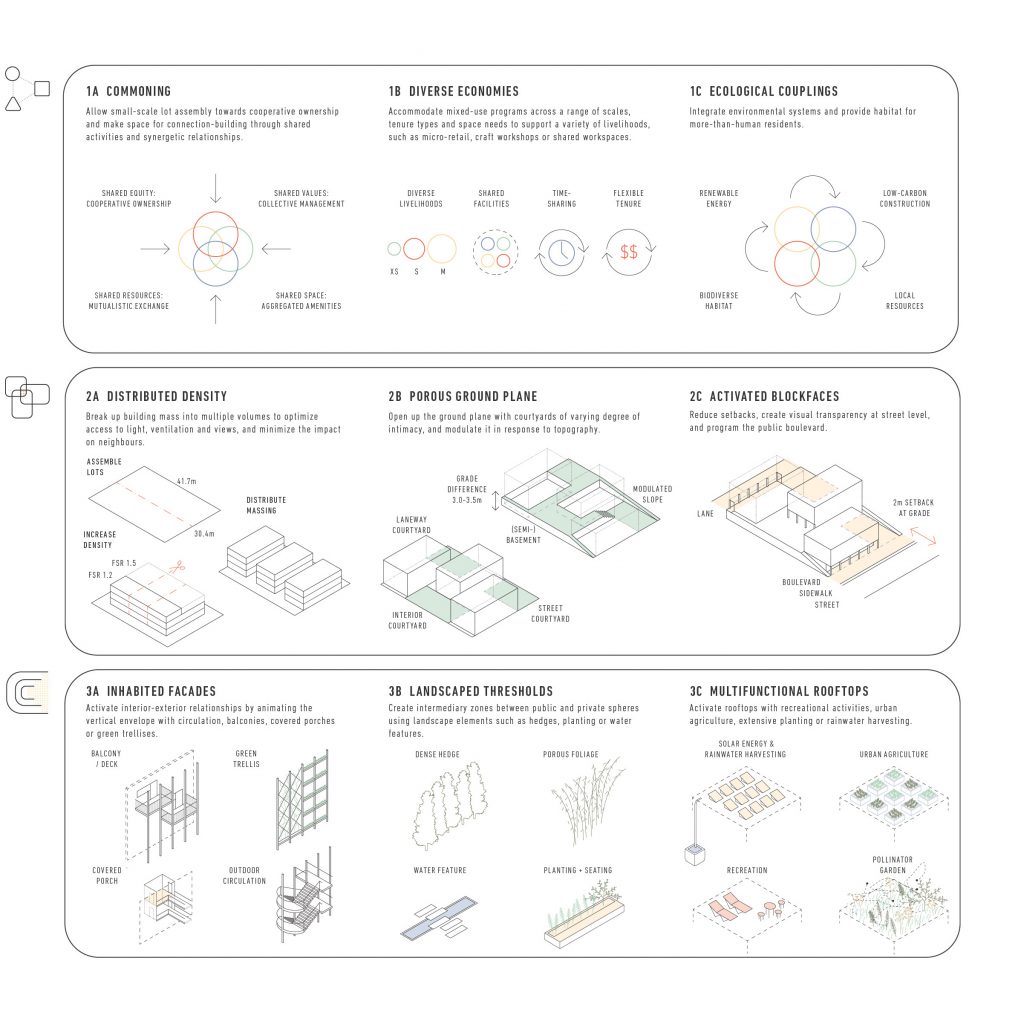

Lots in Common is a series of spatial protocols rather than a rigid, standardized building prototype. Its deployable design moves can adapt to varied scenarios, using them to weave together the many systems and inhabitants of the sites. These design moves harness the diversity of the site’s inhabitants, livelihoods and needs—encouraging convivial and synergetic relationships.

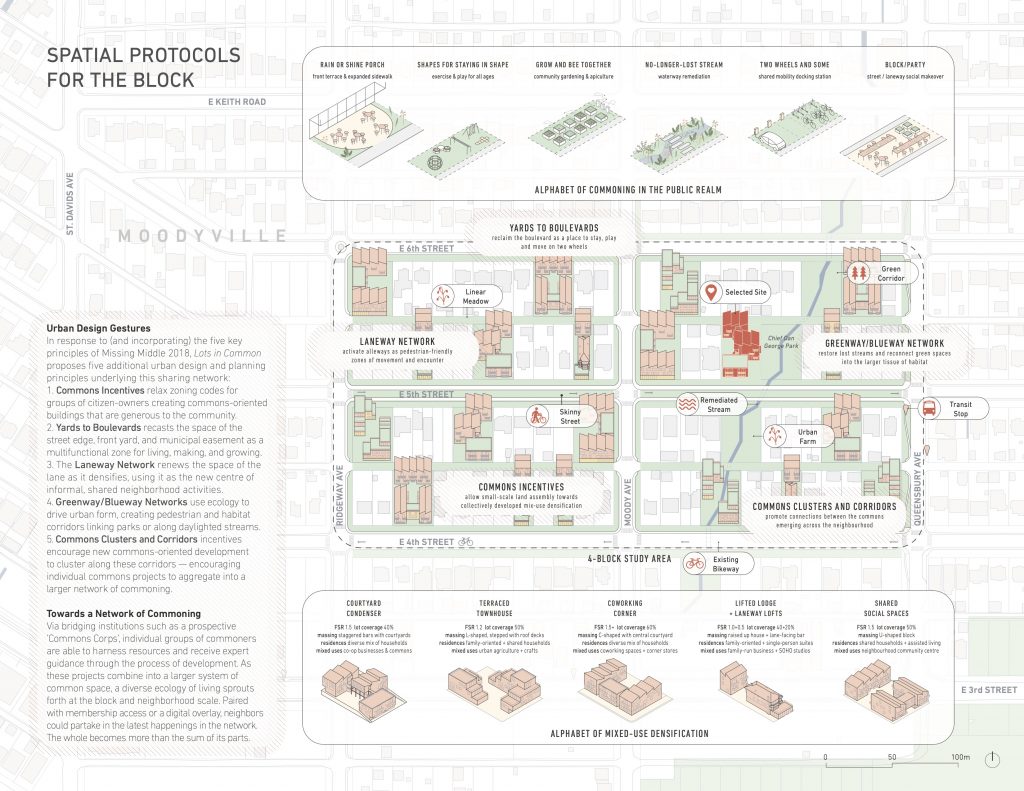

Urban Design Gestures

In response to (and incorporating) the five key principles of Missing Middle 2018, Lots in Common proposes five additional urban design and planning principles underlying this sharing network:

1. Commons Incentives relax zoning codes for groups of citizen-owners creating commons-oriented buildings that are generous to the community.

2. Yards to Boulevards recasts the space of the street edge, front yard, and municipal easement as a multifunctional zone for living, making, and growing.

3. The Laneway Network renews the space of the lane as it densifies, using it as the new centre of informal, shared neighborhood activities.

4. Greenway/Blueway Networks use ecology to drive urban form, creating pedestrian and habitat corridors linking parks or along daylighted streams.

5. Commons Clusters and Corridors incentives encourage new commons-oriented development to cluster along these corridors — encouraging individual commons projects to aggregate into a larger network of commoning.

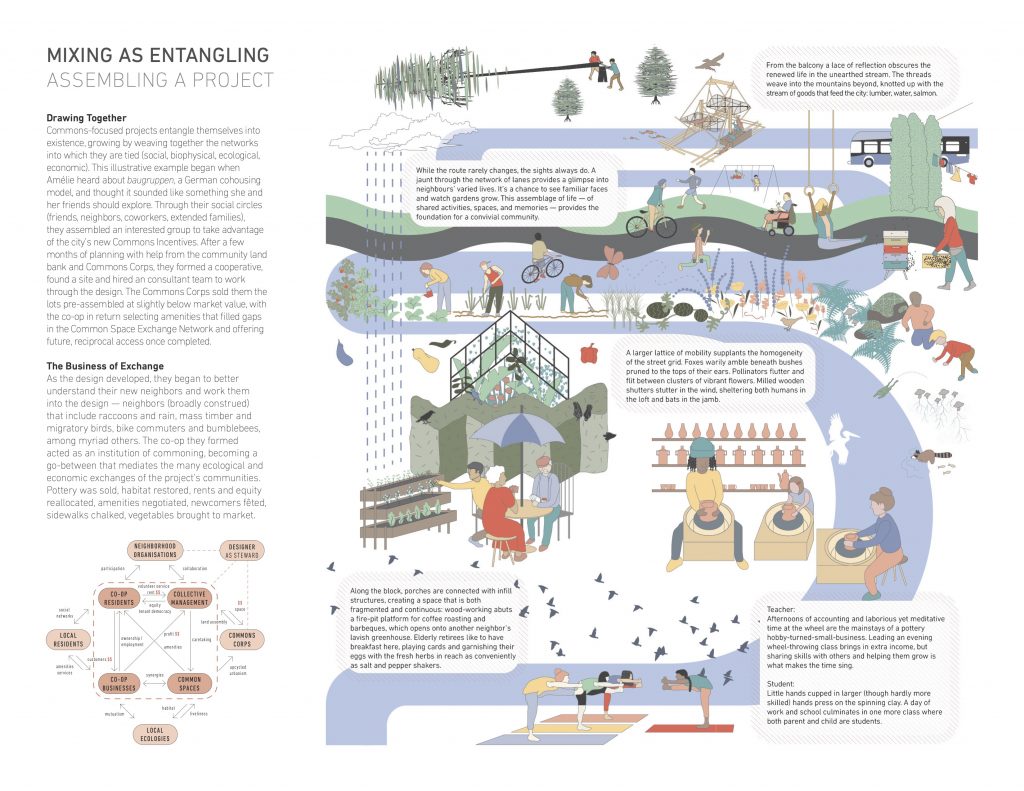

Drawing Together

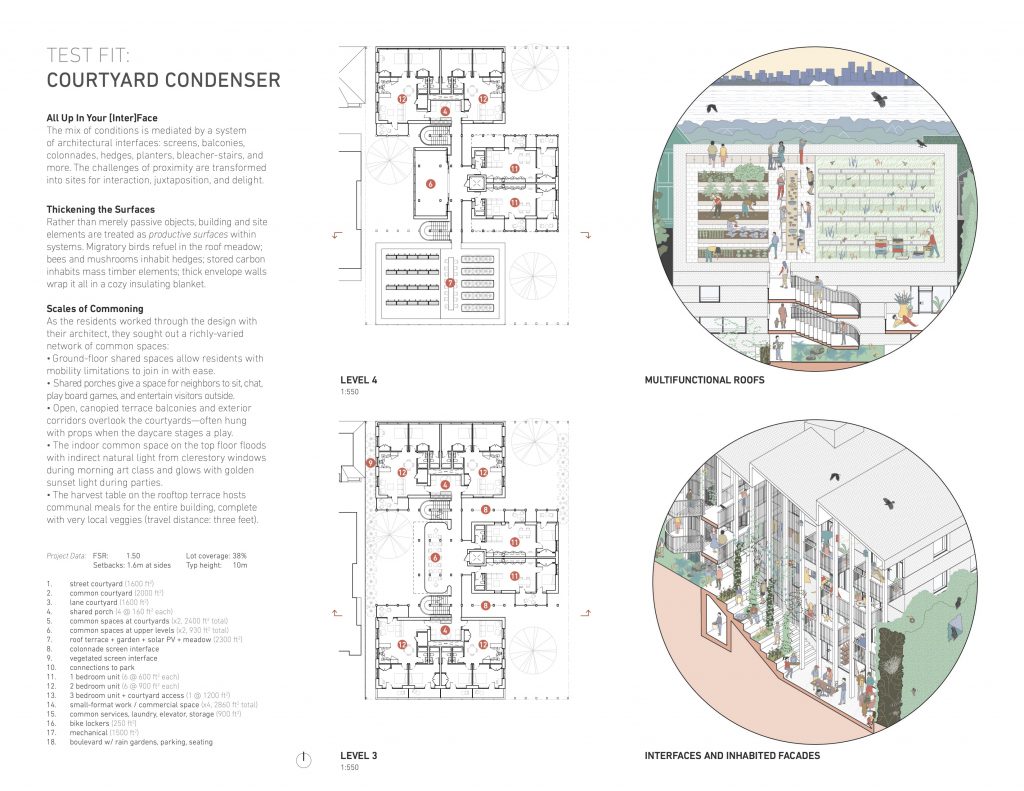

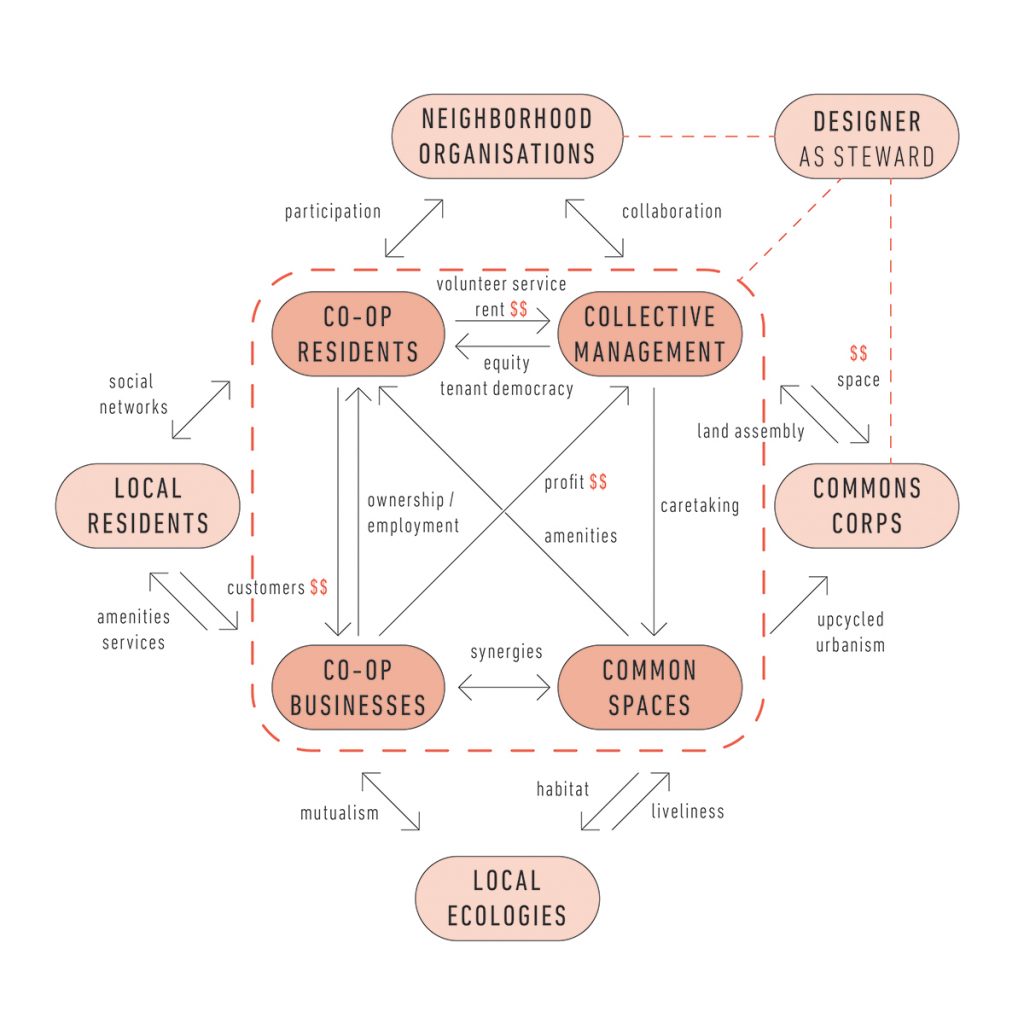

Commons-focused projects entangle themselves into existence, growing by weaving together the networks into which they are tied (social, biophysical, ecological, economic). This illustrative example began when Amélie heard about baugruppen, a German cohousing model, and thought it sounded like something she and her friends should explore. Through their social circles (friends, neighbors, coworkers, extended families), they assembled an interested group to take advantage of the city’s new Commons Incentives. After a few months of planning with help from the community land bank and Commons Corps, they formed a cooperative, found a site and hired an consultant team to work through the design. The Commons Corps sold them the lots pre-assembled at slightly below market value, with the co-op in return selecting amenities that filled gaps in the Common Space Exchange Network and offering future, reciprocal access once completed.

The Business of Exchange

As the design developed, they began to better understand their new neighbors and work them into the design — neighbors (broadly construed) that include raccoons and rain, mass timber and migratory birds, bike commuters and bumblebees, among myriad others. The co-op they formed acted as an institution of commoning, becoming a go-between that mediates the many ecological and economic exchanges of the project’s communities. Pottery was sold, habitat restored, rents and equity reallocated, amenities negotiated, newcomers fêted, sidewalks chalked, vegetables brought to market.